The following story was originally published in Benji Knewman 2.

Masha is Ukrainian. There just isn’t any other way to start her story.

Through the centuries and especially in modern times creative people have been somewhat lucky. They have the means to get the horror of war – or any horror for that matter – out of their systems by simply translating it into their art. And yet it’s much harder for them because they think too much. And let the horror creep in from inside.

But here in London all is fine and somewhat calm. The night prior to this talk, Masha finished her Master’s collection at Central Saint Martins and this is where we are at the moment. It’s very late. In a while we will hear a distant voice on intercom notifying that the school premises are to be closed in 15 minutes. Masha giggles every so often and yet we both know that’s not because she’s particularly joyful. Rather it’s a reaction to weeks and weeks of watching TV news and following events back in Ukraine. That’s where Masha’s home is.

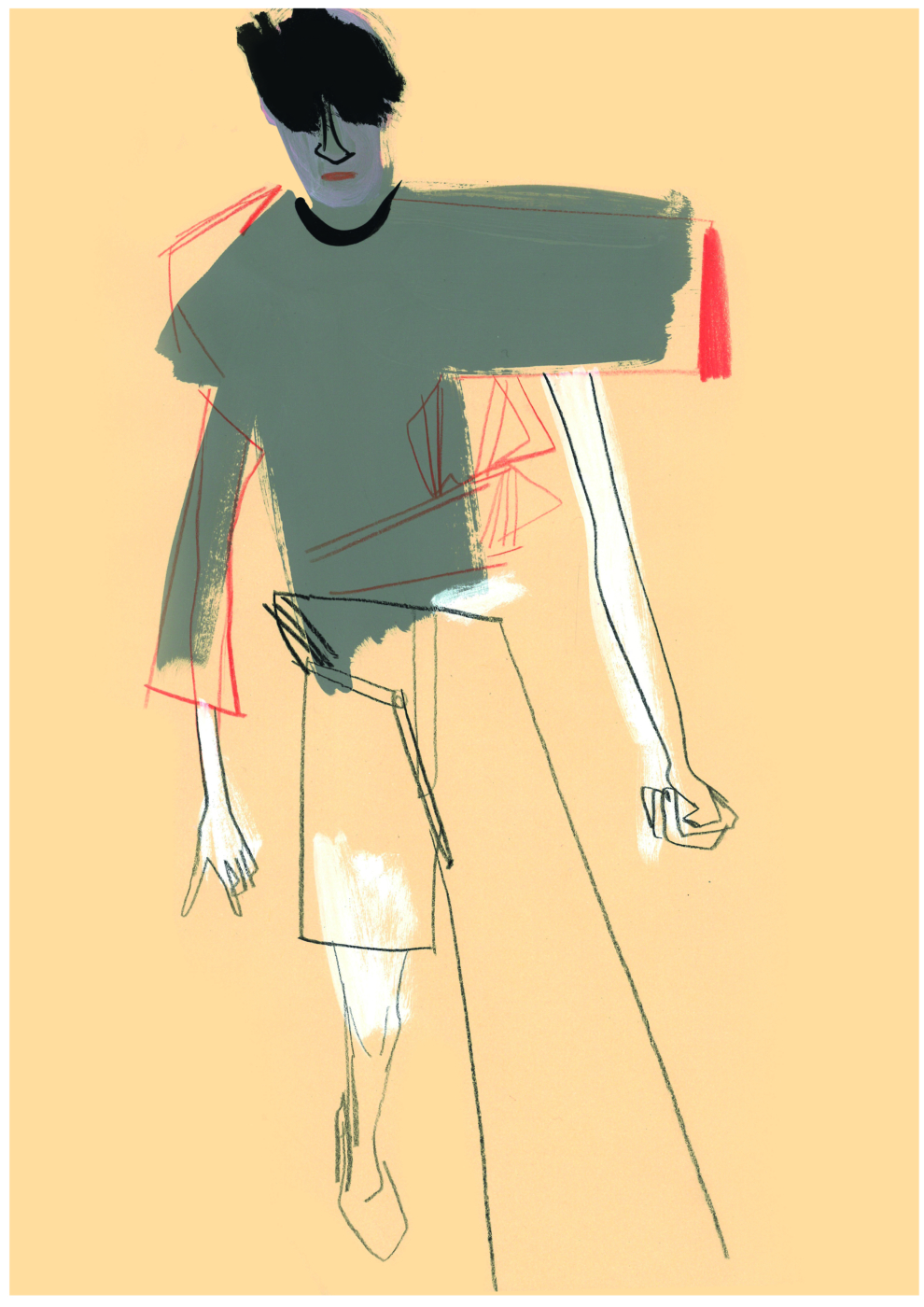

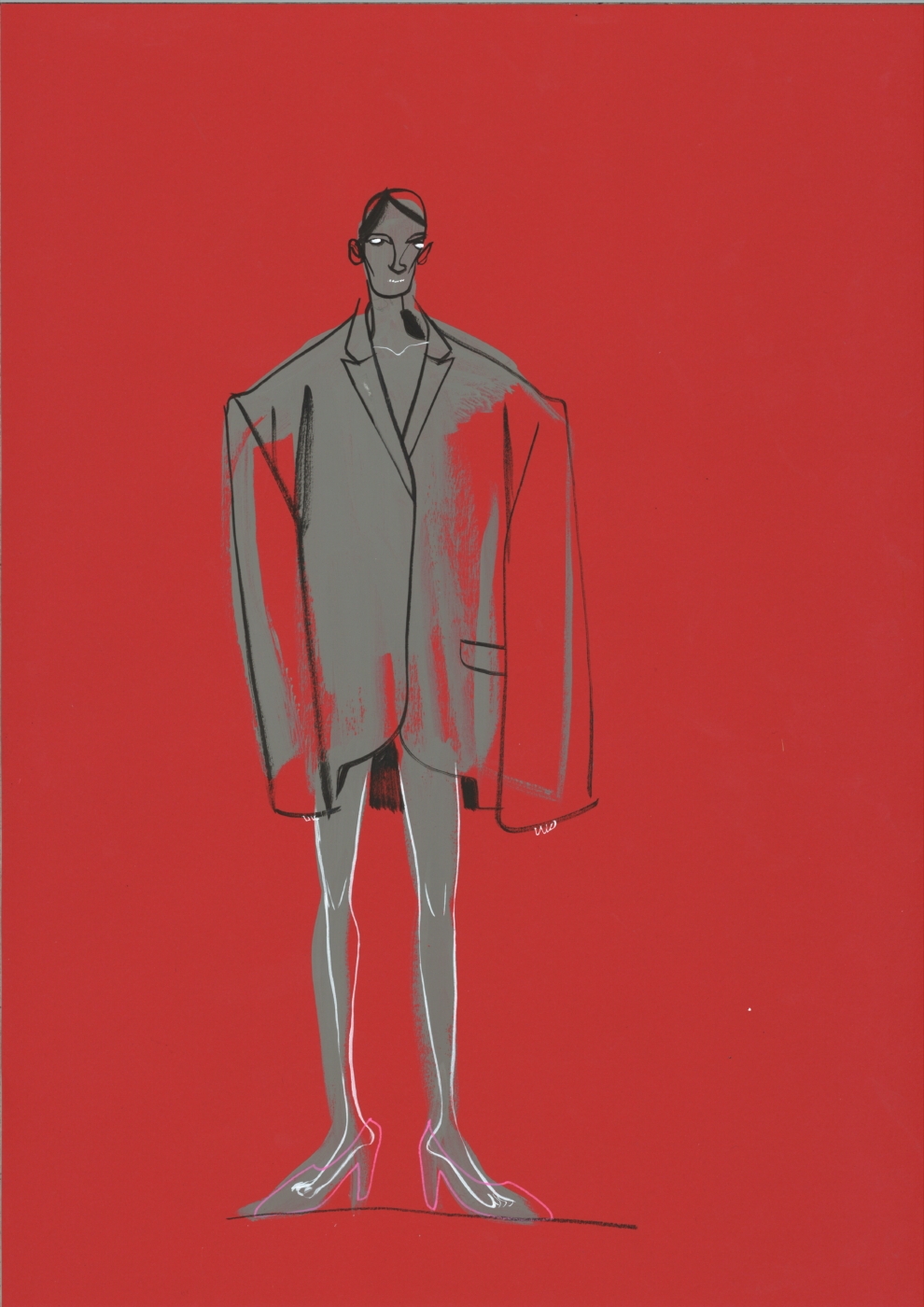

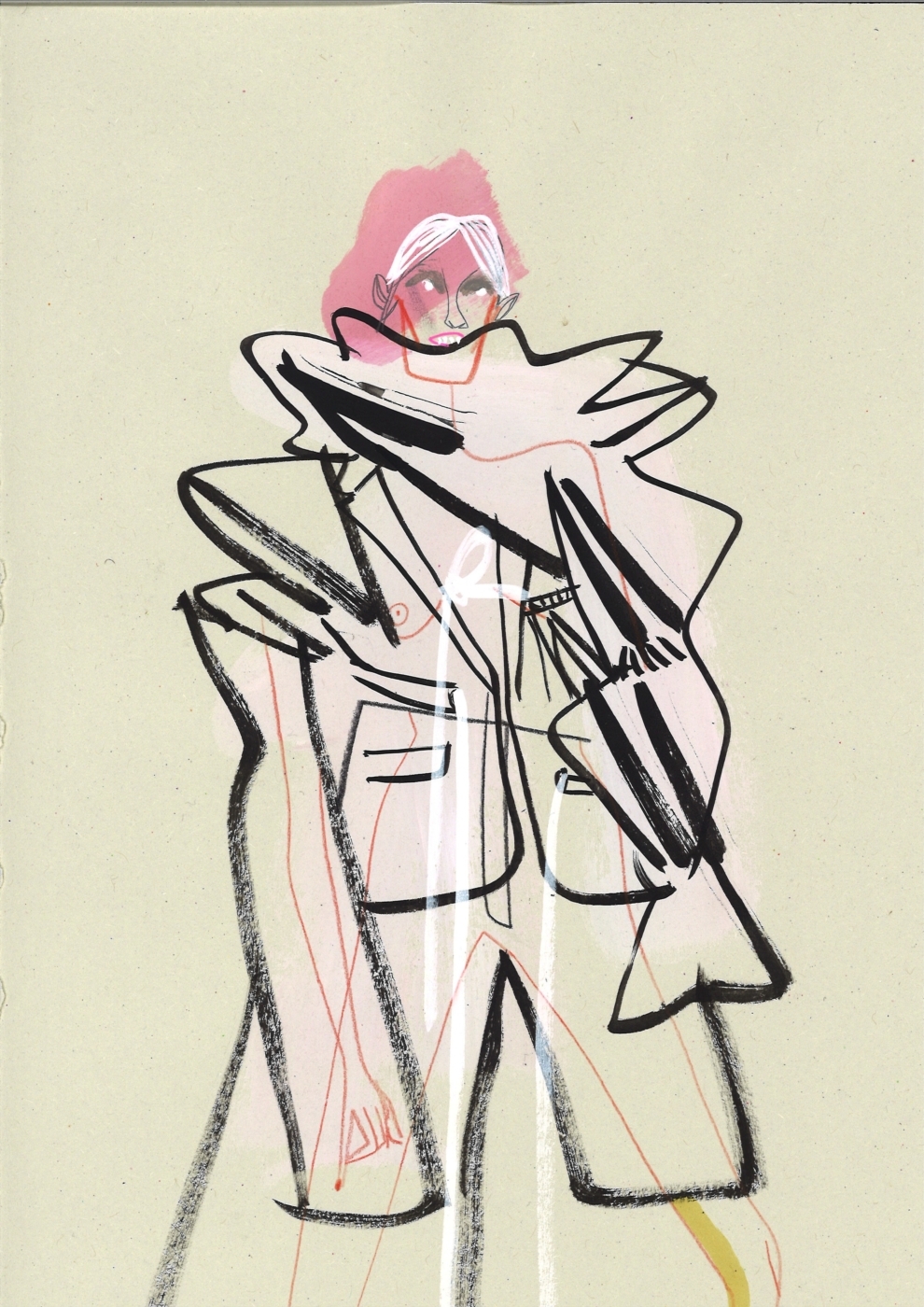

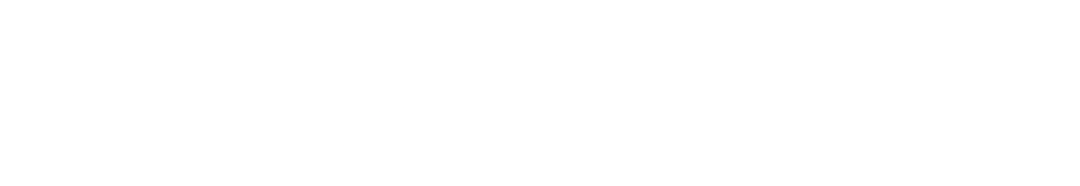

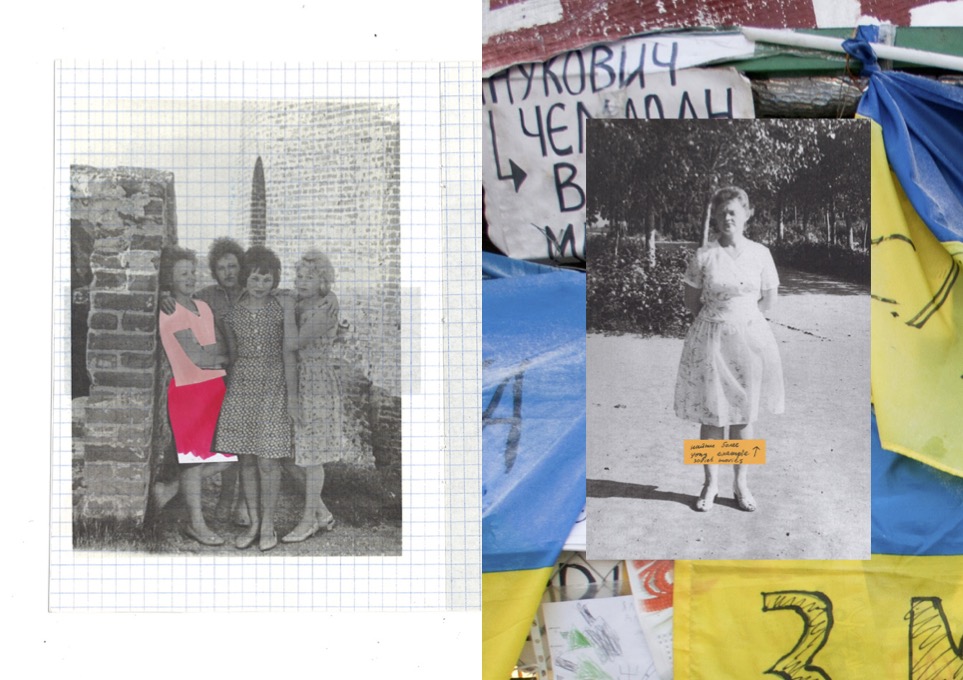

Masha Reva & Ivan Grabko

Masha Reva & Ivan Grabko

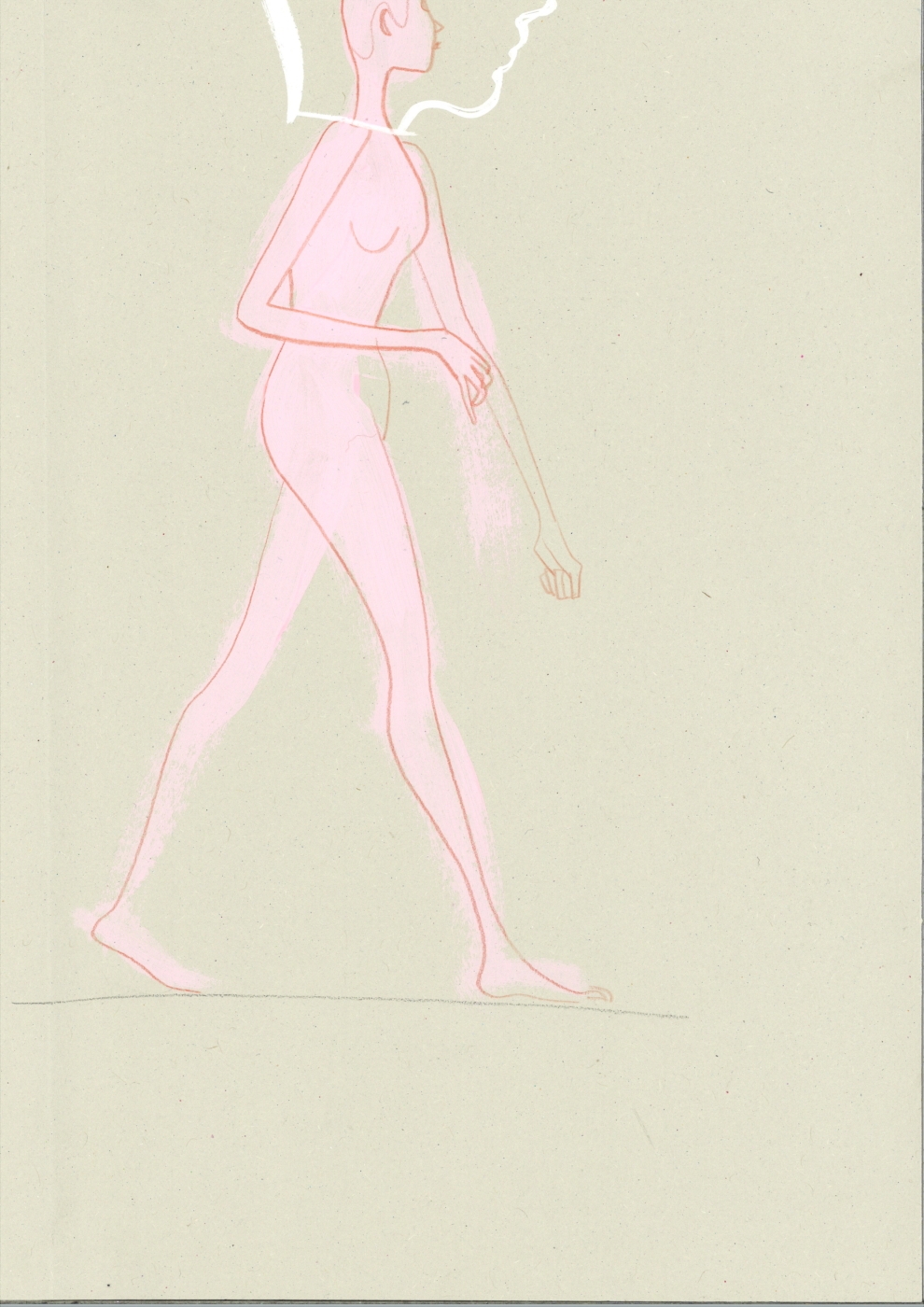

This collection is very different from what I’ve done before. I don’t know why but the main theme is Ukraine – what happened last year in Kiev because I was there when it did. It was very difficult to work with this subject because it’s so personal and I couldn’t think about anything else. My last series of prints called Volya (freedom in Ukrainian) were about this theme as well. But I couldn’t stop. This time I went in deeper, explored the concept of deconstruction and didn’t remain on the surface as in the case with the printed sweaters. I translated this happening into clothes that fall apart and symbol constant change.

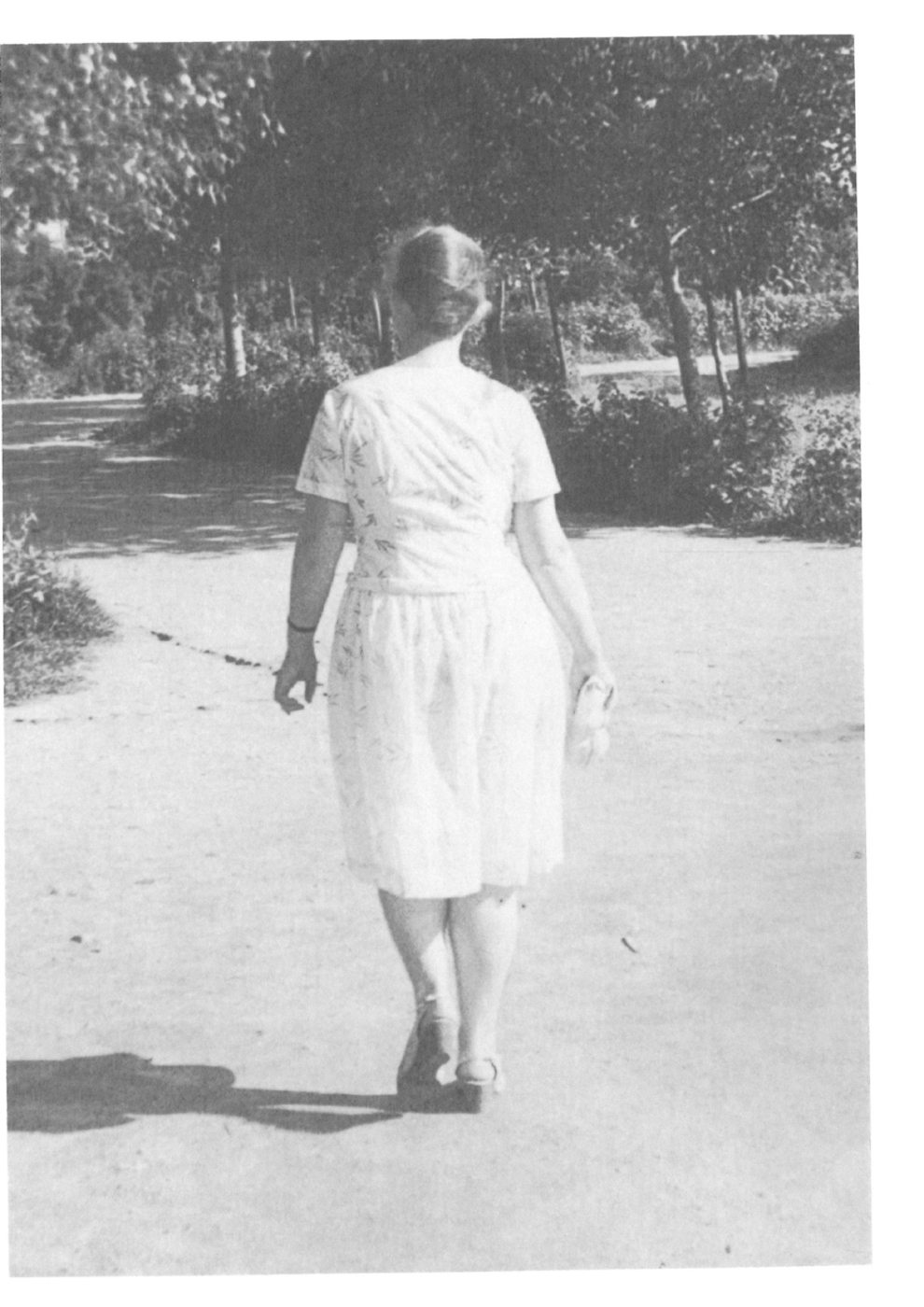

My boyfriend found an old album of photos of Ukrainian people. Most of the pictures have been taken in the mid 50s. This revolution is connected to the past of all these people and it was interesting for me to wonder where they are now. The reason why things in Kiev happened is because we wanted to change the whole system and move to a new world. But the past of these people, their memories, their happy faces, their walks in the nearby park – everything’s in there, in these photos. A memento of time.

But even if it was nice before, it’s time for us to change.

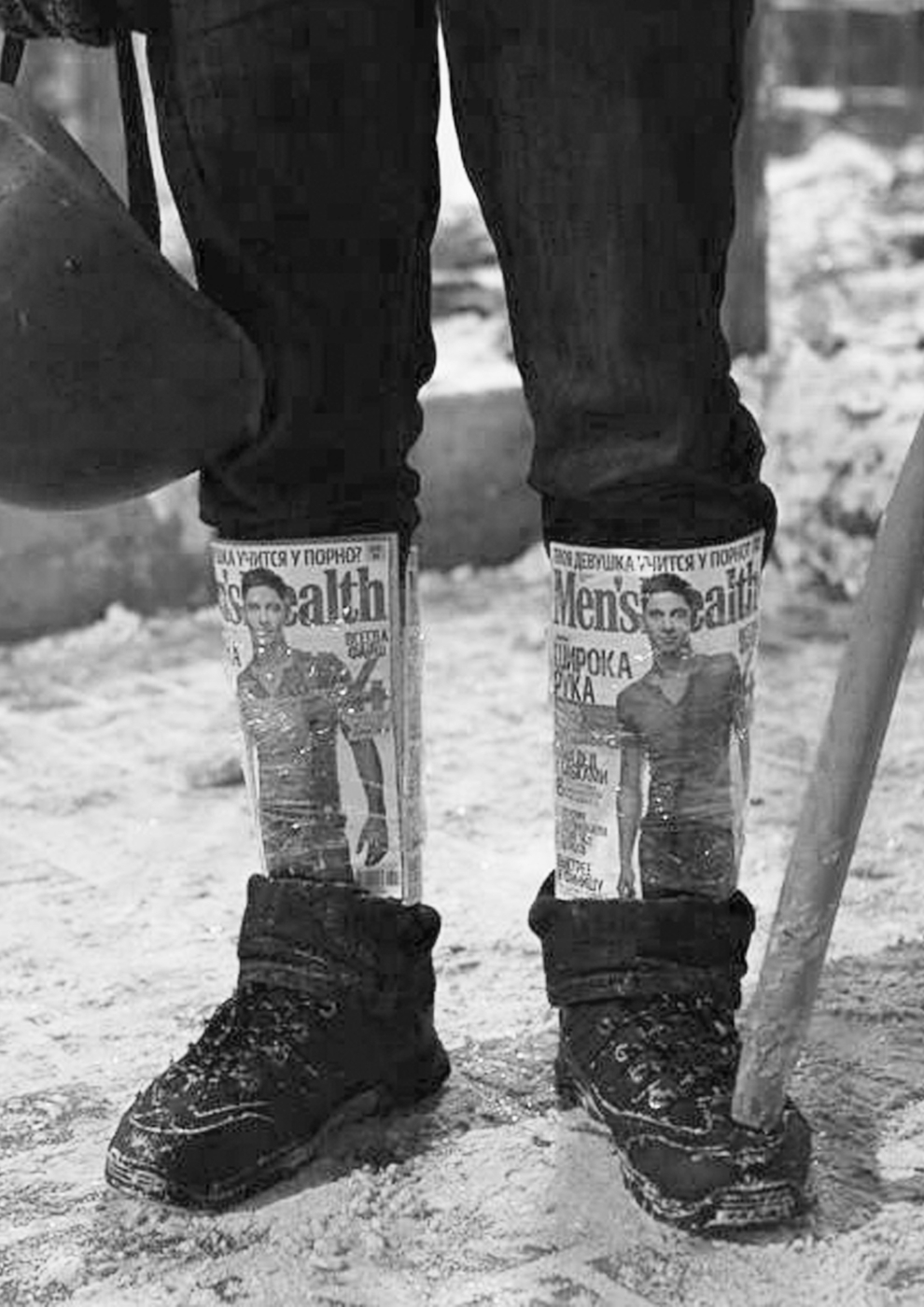

Sometimes it’s hard to explain why I’m doing something. Back in Kiev I walked around the city and watched how people had made tents and DIY barricades. They were no professional artists but what they had produced was so beautiful and raw at the same time. I watched men with copies of Men’s Health magazines attached to their legs like handmade armor – similar to what football players wear on the field. From that was born the main idea for my collection – that the clothes are not comfortable. A classic men’s jacket becomes very deconstructed, while a coat with attached ropes limits the movement of a person.

At first I was a bit confused because fashion is something commercial and often more luxury, people are always buying things and spending money. And here I am, putting this serious idea on the table. I don’t think my collection is commercial at all. It’s simply my feelings and what I wanted to think about. It’s more like an intellectual approach. I wanted to make something special – even if it wouldn’t be sellable. At least I will translate my idea. I want people to think and learn about what’s happening in my country. It’s a psychological approach. I planned that after the Volya Series I’ll let it go and move on to something else but I couldn’t. I hope I can be a more successful designer later, but right now I have to do this.

There’s this photo I got from the Internet – a bad guy is tied to a pole with a transparent duct tape. As people had nothing else on hand they used it to tie him up while waiting for the police. It was really crazy and could only happen there at that time. That picture was another reference for my collection.

I still don’t like what I have in the end – this line of clothing. As I said, it was more like a psychological thing – just a way for me to work it out. Actually it was a struggle.

I was watching news all the time as I was searching for material for the collection. My tutor here at Saint Martins wanted me to have a work system but in this case it was really hard to do that.

I kind of feel they wanted me to be a normal fashion designer and show that I can translate my theme into clothing. But for me, this is a personal context, so it was really difficult. They had a really hard time with me. I couldn’t be normal. I was always stressed because I was in the middle of this thing. At the beginning it wasn’t so aggressive but gradually it became so as many people died day after day. It also became harder and harder for me to keep working on the collection.

Whenever I say I’m from Ukraine people show worried faces and ask how the war is. There’s nothing I can do and yet everybody fights as one can. Maybe me translating this fear and horror – maybe this is my fight. But I don’t want people to be sorry for me. I just have to get over it.

I have a Cinderella slipper here – an oversized shoe made of resin. It’s impossible to wear it, it’ – it definitely put me out of my comfort zone. I have to be personally involved with every project that I make, otherwise it’s just boring. I’ve been wondering do I even belong to the fashion design world because a fashion designer shouldn’t be like that.

A normal designer just picks an idea and translates it quickly into a commercial collection. But I’m not normal. I have to be “worried” about what I’m doing.

My collection is horrifying but there’s beauty in it, too. There was this white vinyl I got from a company in Italy. I laid it out on a men’s jacket and then put it under the heat press. The vinyl melted and somehow glued the sleeves and pockets to the jacket – it became this flat sculpture. It’s like you have all those nice clothes put nicely on hangers in a shop and then suddenly some invincible force hits the store. Like a big blast pressing the jackets together, melting them and changing their shape forever. It’s like a symbol of what happened in Kiev. I also wanted it to look a bit nostalgic. A person is keeping his grandma’s dress or granddad’s jacket – as a keepsake. And then it just gets fucked up.

You may say that this feeling can be understood only if actually experienced by the viewer, but I’d argue here. Years ago I saw the collection by Hussein Chalayan. On the catwalk there was a family – grandparents, parents, a girl and her sister. They were sitting still on chairs. At one moment they got up as if they had to go and suddenly you see that their clothes are cut in a way that when they stand up, the shape of a bent leg – the sitting position – is still there, designed into the fabric of their clothes. Chalayan’s homeland was also at war, so he had to move away. With this collection he tried to show that he and his people – they didn’t want to go but they had to.

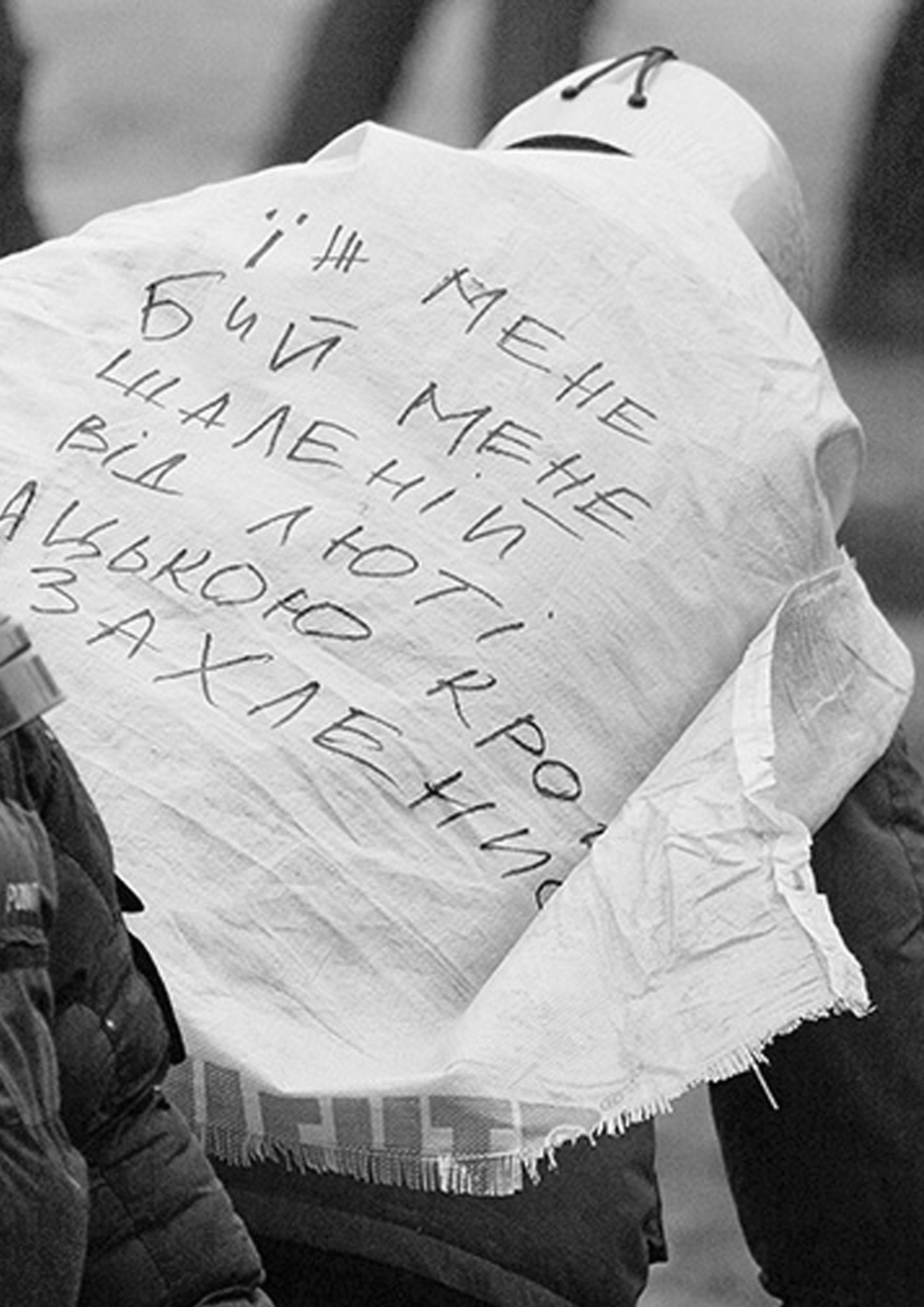

For the last seven years I’ve been living mostly in Kiev. I moved there from Odessa when I was 17. Then I studied and did internships. This year I took out to come here to London to finish my MA at Central Saint Martins College. In Kiev I lived in a flat which was only 15 minutes walk from Maidan (Independence Square) Some of the photos here in my zine accompanying my collection, I took myself. My friends and I had never experienced this kind of aggression and so we didn’t have fear, at least not so that we would stay home. We marched the streets protesting although I myself wasn’t the super activist. At the first stage I was more an observer.

At the first stage I was more an observer. I had never seen anything like that, I was intrigued and wanted to know why this is happening.

My friends and I were sure Ukraine had to move towards Europe. When something like that happens, it’s so powerful you can’t help but go out and take pictures. It’s very personal. Your country, your city, your people.

All the time there was live stream news in the background and it was hard to watch. The clashes between protesters and the police happened mostly at night, and in the day we went back to the square. At night mostly men stayed there as it was too dangerous for women. Like a terrifying reality TV show and you’re part of it. It’s really hard to take yourself out of it because everyone is in it. It becomes part of your work, part of your life, you couldn’t get away. Even here – I’m in London but my brain is back there. I’m not watching the news so much anymore as I’m just too emotional, too nervous now. If I’d watch everything I’d become crazy. You can’t help them and only become stressed.

Then again, you can go help or stay home and be horrified. A lot of my friends became volunteers but I couldn’t. I couldn’t be there all the time.

Maybe this is my way to help. This is my tool to show that fashion isn’t only made to be sold. It’s a shape I’ve put my feelings in.

I have this story with the Ukrainian flag. Three months before it all started we weren’t that patriotic as a nation at all, but it made us so. When the first victims perished, we were all really shocked. I decided to put my Ukrainian flag on the balcony. However, it wasn’t really a good idea as it was dangerous timing. My father – he’s a sculptor – he was scared that titushki (unidentified men in civilian clothes with an aim to intimidate and disperse demonstrations by opponents of the Ukrainian government, and attack participants and representatives of the media – author’s note) would see it and found out where I lived and something bad could happen. But I was really stubborn and refused to take it off. My parents share my feelings and opinion, they were just scared – as any parent would be. I mean, some days it was advised not to go outside after 9PM and we took taxis only to go a couple of blocks.

The whole flag on the balcony thing – it wasn’t something to draw attention or show off. It was only a natural reaction. I think for people on the street it was also some form of giving courage, like there’s somebody else sharing their opinion and they shouldn’t be scared, that they’re not alone. After a while other flags appeared on the balconies on my street. Although I wouldn’t say it was because of me.

I know my collection is reminiscent of work by Rei Kawakubo and Martin Margiela because they were also working with deconstruction. One would say it’s already been done a hundred times. And yet I couldn’t do it any other way. Then again, everything has already been done in the arts and fashion. This was my personal project I had to do. Like a diary.

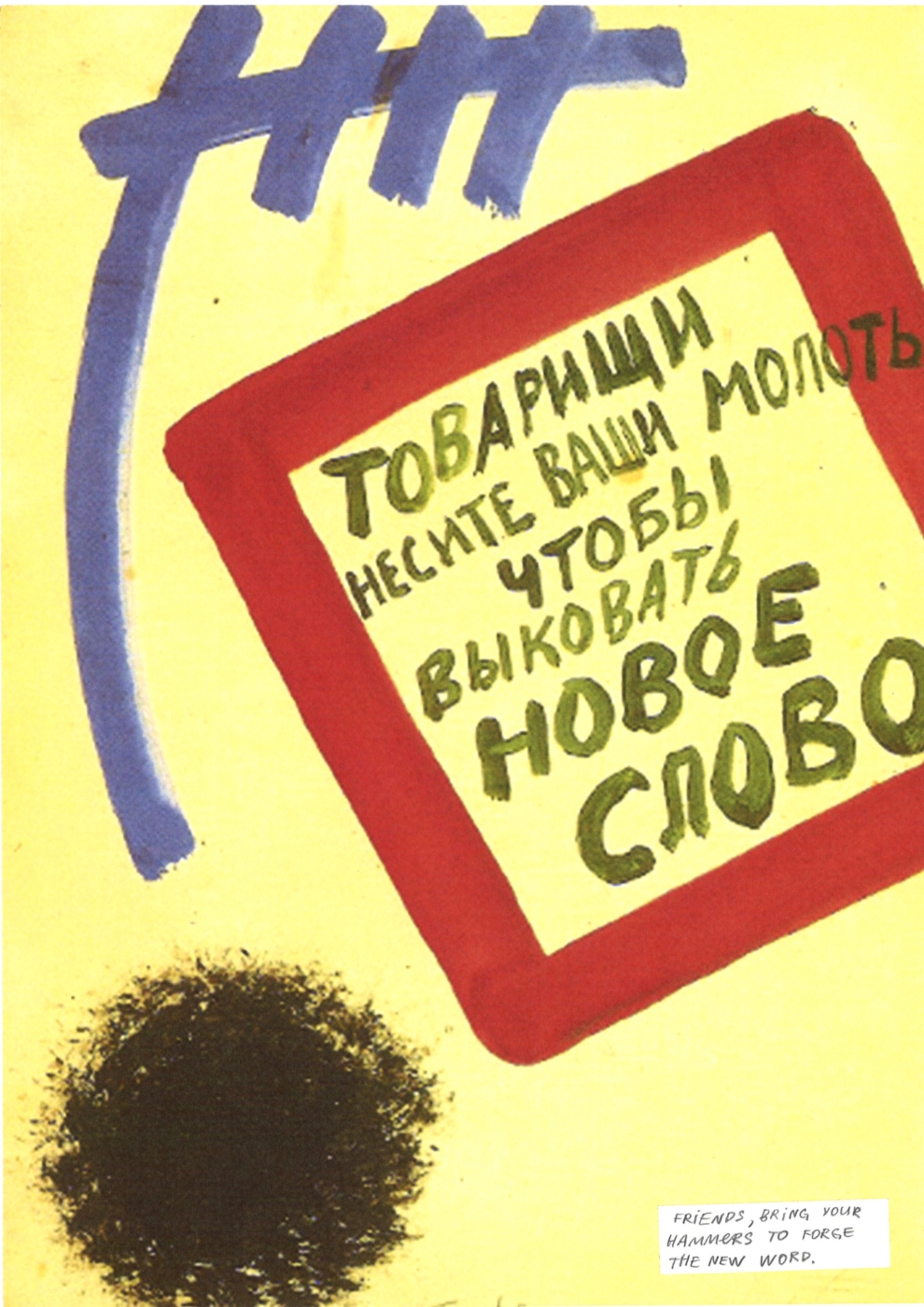

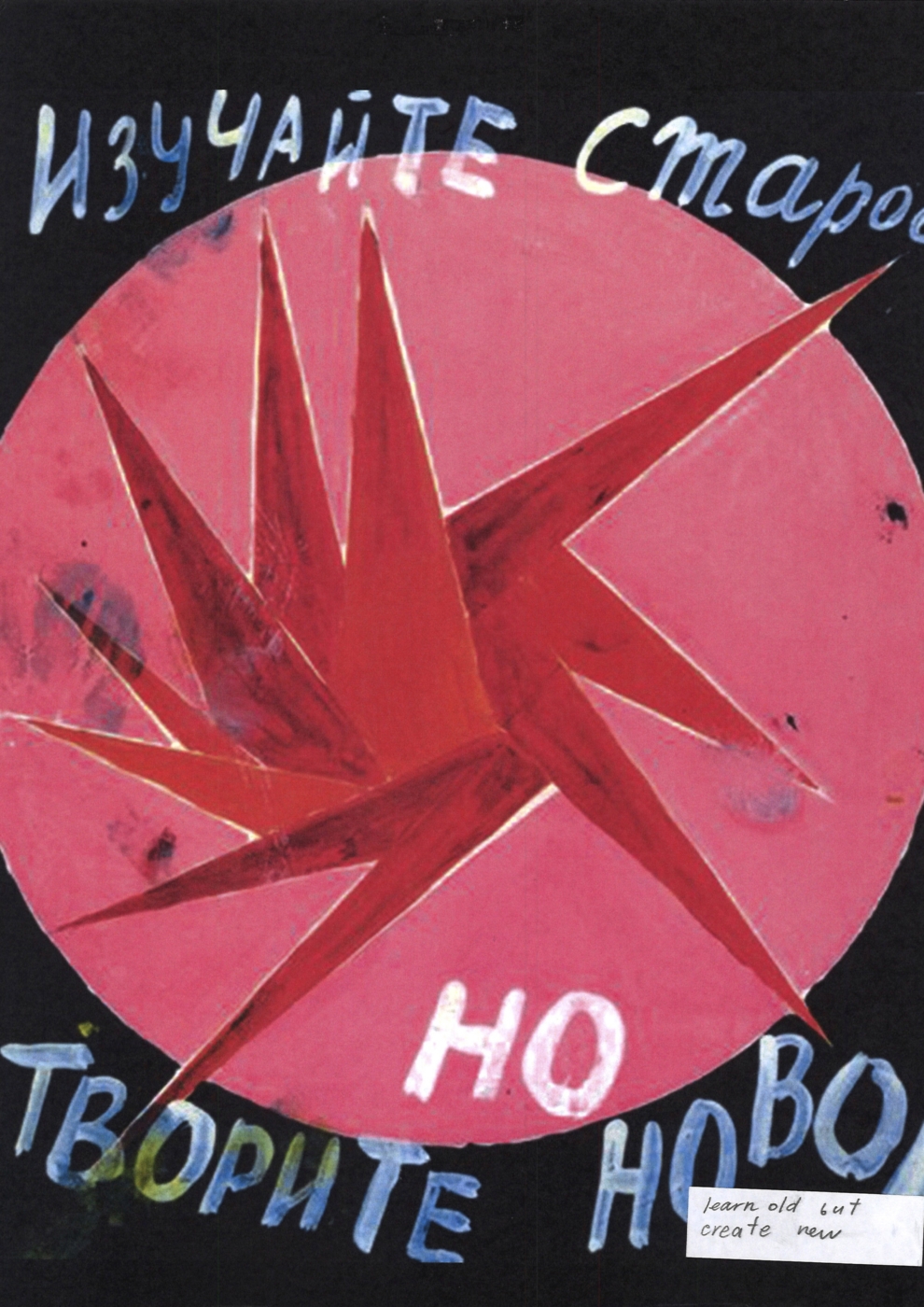

For my project I took a closer look at the posters by Varvara Stepanova, a Russian constructivist artist – at the time it was something new, something fresh. I wouldn’t say that what is happening in Ukraine is something good, but it’s this energy that I like.

In a way, you need something dramatic, like to go through an illness so that you can heal yourself and then become a new, stronger yourself.

At their time, constructivists couldn’t even imagine in what point their art movement will end. Neither do we in Ukraine know what will happen and where it will all end. That’s why my work is more like a documentary, there’s no statement – like this is all going for the best. It’s just how it is right now.